'A Very No. 10 Cock-Up': How Labour Misread the Room on Welfare Reform—and Opened the Door to a Confidence Crisis It Can’t Spin Away

The enormity of Vicky Foxcroft’s resignation from Starmer's cabinet last week needs to be appreciated and understood.

As I wrote previously, there are both upsides and downsides to the way government communications—the so-called ‘Comms Grid’—can be wiped clean from the agenda without notice.

Strength Abroad, Surrender at Home: How Labour Intends to Manage Decline in a Flak Jacket

With tensions escalating in the Middle East and the situation deteriorating by the day, it’s hard to believe that, less than a week ago, most of Britain’s political rune-readers were still poring over the entrails of Rachel Reeves’ Spending Review.

The official comms plan—what ministers hope will lead the news—rarely survives first contact with reality. A carefully laid media schedule can be upended overnight by a fresh controversy, or simply by the grim churn of the news cycle itself.

Monday morning, for example: do voters remember how the government proudly unveiled plans to slash green levies for thousands of British firms, aiming to reduce energy costs and kick-start a long-stagnant manufacturing sector? A central plank of their long-awaited industrial strategy?

It’s extremely unlikely. The story didn’t even survive the morning. It was overshadowed first by international events—namely, the conflict in the Middle East—and then by the sheer weight of everything else the political week had in store.

The point is: Breaking the ‘Comms Grid’ is convenient if you’re trying to smother a brewing rebellion on your backbenches, the resignation of an important minister, or quietly beginning to backpedal on policy. It is less so, however, when you're desperate for voters to notice a supposed long-term economic boost that feels entirely abstract next to short-term reality.

In the case of Foxcroft’s resignation, it was the former. It didn’t cut through either.

And it should have.

Foxcroft’s was a principled resignation over a distinctly Labour issue: welfare reform. It should have made waves. In more unstable times, it might have dominated headlines for days—or, under a weaker government, signalled the beginning of the end.

Instead, it sank—almost completely—beneath the tide. Not because it lacked substance, but because in a media environment already saturated with grief, outrage, and rolling updates from abroad, the Labour leadership had no incentive to amplify a domestic problem. Nor did most of the press.

This is the double-edged nature of a broken grid.

When the news agenda is volatile or already overloaded, even genuinely significant developments can vanish before they’ve had a chance to register. That can be extremely useful if you’re looking to bury a story. A resignation, a rebellion, a wobble in the policy line—it disappears into the static.

It works both ways, however.

If you're trying to tout a long-term strategy—“billions in investment,” “a bold new vision for industry,” or whatever slogan has been cooked up that week—it rarely lands when voters are preoccupied with more immediate pressures: rising council tax, shuttered local services, or the sheer bleakness of the international mood.

In Foxcroft’s case, the silence surrounding her exit was telling. Labour didn’t need to spin it. The moment passed with barely a murmur, drowned out by louder headlines.

But—

The underlying issue remains: a frontbench resignation doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It signals deeper unrest inside the PLP where the mood is growing more fractious by the day.

In days gone by, the resignation of a government whip would have been a flashing red light: a sign that the administration was running on fumes—fractured, undisciplined, and incapable of consensus.

Vicky Foxcroft’s job, after all, was to enforce party discipline—to ensure MPs voted with the government. That she herself chose to resign from the cabinet says everything.

In Foxcroft's individual case, as her letter makes abundantly clear, she “[did] not believe that cuts to personal independence payment (PIP) and the health element of Universal Credit should be part of the solution” to Labour’s planned welfare reforms. Her position was therefore untenable.

Foxcroft was not alone.

Over one hundred Labour MPs signed a letter backing an amendment that would have killed the bill—had the government’s plans reached a vote.

Their dissent followed earlier attempts to secure concessions, some of which I covered last week. It also followed the government's aggressive use of the whip.

Threats were allegedly made: deselection, withdrawn campaign funding, curtailed career prospects, even suspension from the party. Others were instructed merely to abstain. The threats soon turned to “begging and flattery,” and the whipping operation became half-hearted at best. Few were persuaded. Fewer still were impressed. Among the unimpressed, reportedly, were a dozen ministers still serving in Starmer’s cabinet.

A meeting took place between Liz Kendall and ‘unimpressed’ MPs on Monday evening.

Some MPs expressed that if the government did not backpedal on its plans, a vote against would not only kill the bill, but would also effectively end Keir Starmer’s premiership. Similar warnings emerged from Downing Street into Tuesday, and dissenting MPs were warned that the vote would be treated as a de facto confidence issue that ‘could’ trigger a general election.

There is naturally more context to this.

For months, frustration has been building in the PLP—not only over welfare policy, but over the trajectory of the government’s entire strategic direction.

Backbenchers complain of minimal engagement from Starmer and his team. Some MPs say they’ve never met the Prime Minister, despite having helped deliver Labour’s landslide in 2024.

Downing Street, preoccupied with global crises—from Middle East conflict to the destabilising return of Donald Trump—has admitted its difficulty in telling a coherent domestic story. The subsequent narrative vacuum has widened the distance between party leadership and its own MPs.

After May’s local elections, the complaints grew louder.

MPs pointed to the Winter Fuel Allowance debacle, the two-child benefit cap, and among other things repeated delays on renters' rights and workers' rights reform. Policy has not trickled down to the ‘Change’ that was promised.

This “tin-eared” approach is increasingly seen by some as arrogance that raises a more fundamental question: if Labour won’t listen to its own MPs, why would it listen to voters?

Remember—

Those who read Foxcroft’s resignation letter will have noted what was perhaps the most damning line contained within: “I have wrestled with whether I should resign or remain in the Government and fight for change from within.”

The subtext of this is plain: Foxcroft did try to make her case from within—she was ignored, and met with intransigence.

Her departure speaks less to personal misgivings than to a party leadership unwilling to engage constructively with dissent, even from someone with deep experience advocating for disabled people. All the while protestation within the party had been steadily building since July 2024 when Liz Kendall* launched the so-called “blueprint for fundamental reform.”

*That’s Liz Kendall, “the cabinet’s grim reaper” according to Labour MPs.

Foxcroft, evidently, wasn’t simply wrestling with principle. She was wrestling with power that refused to listen despite evidence (from charities, firstly, concerned about the impact of the cuts), despite the lack of credible economic rationale, and despite the political fallout many Labour MPs seem acutely aware of.

By the middle of the week, the government were in such a quandary that it was set to have to rely on Conservative votes for the bill to pass, albeit on three conditions:

The Conservatives said that the welfare budget is too high and the bill put forward by the government must indicate that it intends to bring it down.

The Conservatives said that the bill must give a clearer indication that the bill will be effective in getting people back to work. Currently, they argue using the government’s own impact assessment, it does not.

The Conservatives would only support the bill if it meant that it would see no new tax increases in the Autumn budget. This too, with the UK’s current

unfunded spending commitmentpledge to spend 4.1% of GDP on defence by 2027 (up from 2.6 percent) meaning tax rises are inevitable - seems unlikely.

The support, then, was perpetually in doubt.

But if the Conservatives alongside other opposition parties did support the bill, it could be politically damaging and extremely embarrassing for the government to rely on the votes of opposition parties to pass what is considered a flagship piece of legislation in SW1.

It quickly became clear that the government had been caught off-guard by the scale of the rebellion—and the level of support for the reasoned amendment. Joining the rebels and compounding the problem further were two powerful Labour figures: Mayor of London Sadiq Khan and Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham.

Speculation began that the vote would be delayed while Downing Street scrambled to offer concessions. The mood inside No. 10, by all accounts, was one of panic.

It’s worth remembering: the government wanted to be talking about something else entirely. In the middle of what increasingly looks like a global unravelling—and with nobody seemingly knowing “what the fuck they’re doing”—Labour had hoped to shift the focus to defence.

But as with the industrial strategy rollout earlier this week, the government’s national security push was knocked off the Comms Grid before it had a chance to land. This time, it wasn’t international turmoil that broke the message—it was the rebellion brewing inside Labour’s own ranks.

So while Keir Starmer—like a parent who’d left the children in the care of a well-meaning but out-of-their-depth babysitter (in this case, the Labour whips' office and Treasury enforcer Pat McFadden)—was in the Netherlands at the NATO summit, earnestly discussing Britain’s war-readiness, the children back home had gone feral.

Enter Angela Rayner.

Speculation has been building for some time that Rayner could emerge as the favoured candidate to replace Starmer, should a confidence vote ever materialise.

It’s interesting, then, that she would double down on the government’s timetable for the contentious legislation—particularly amid suggestions that the vote might be delayed or pulled entirely.

Rayner insisted the vote would go ahead on Tuesday, echoing Starmer’s own defiant stance.

At this point in what was becoming the patented Keir Starmer climbdown, the only real option left appeared to be offering further concessions. By Thursday, there was little sign that rebels had been placated. If anything, the numbers were still growing.

And so, predictably, the blame game began.

Some pointed the finger at Starmer and Rachel Reeves. One Labour MP said:

“He marched us up the hill on grooming gangs, he marched us up the hill on winter fuel—I’m not going out to insist the welfare changes are still going ahead when I could be embarrassed by a climbdown any moment.”

Others have blamed chief whip Sir Alan Campbell for the debacle.

Others turned their fire on Starmer’s and chief-of-staff, Morgan McSweeney. His data-led approach to policy—designed to appeal beyond Labour’s core vote—has underpinned much of the government’s current direction. According to internal critics, this strategy, sometimes referred to sarcastically as ‘Morgan’s Long-Game’, has dominated Labour’s thinking.

But, as one MP put it:

“Everyone is selling shares in Morgan. People are starting to put their heads above the parapet and say maybe he’s not the Messiah after all.”

In truth, the blame likely lies elsewhere. As one backbencher summarised bluntly:

“This is a No. 10 fuck-up.”

Whether for failing to read the room, or for ignoring months of dissent from within the PLP, the problem isn’t simply policy—it’s leadership.

Crucially, many of those who signed the amendment weren’t members of the Socialist Campaign Group or the usual suspects on Labour’s left. Around 40 rebels came from the 2024 intake—handpicked, carefully, fastidiously, by McSweeney’s own Labour Together operation, vetted precisely for their loyalty to the Starmer project, and helped along (as noted previously) and bought off with tens of thousands in campaign donations.

Others were so-called ‘soft-Left’ or centrist MPs—who joined the Labour movement explicitly on the basis of opposing Tory welfare cuts and austerity. They didn’t join Labour to pass a Reeves spending review that clawed back billions from the sick and disabled.

Reeves’s strategy, then—seen in both the Autumn Budget and her Spending Review—was always going to cause friction if it relied on growth carved from cuts to the most vulnerable in this context.

Rebels argue that was the whole point. The bill, they say, was never really about reform. It was a scramble to find £5 billion in crude savings to keep Reeves within her self-imposed fiscal rules.

Downing Street’s approach has been marked by arrogance and what many describe as a “bunker mentality.” Even as late as Thursday, Starmer was urging MPs to “read the room” and dismissed their protests as “noising off”—only reinforcing the sense that his operation had stopped listening.

The truth is then perhaps once again a government where the fish rots from the top. In that sense, the only person left to blame is Starmer himself. It’s one of the reasons the whole thing was being treated, by some, as a de facto confidence vote in his leadership.

Whether or not a formal confidence vote actually materialises, the political reality had already shifted by Thursday evening. A rebellion on that scale—cutting across factions, generations, and loyalties—was not supposed to happen under Keir Starmer. Certainly not this early into his premiership, barely a year in.

And yet, there it was.

The cracks were no longer theoretical. They were visible, widening, and being watched closely—not just by MPs, but by party members, the press, opposition parties, and most dangerously of all: voters.

By Friday, the government had blinked. Or at least sort of.

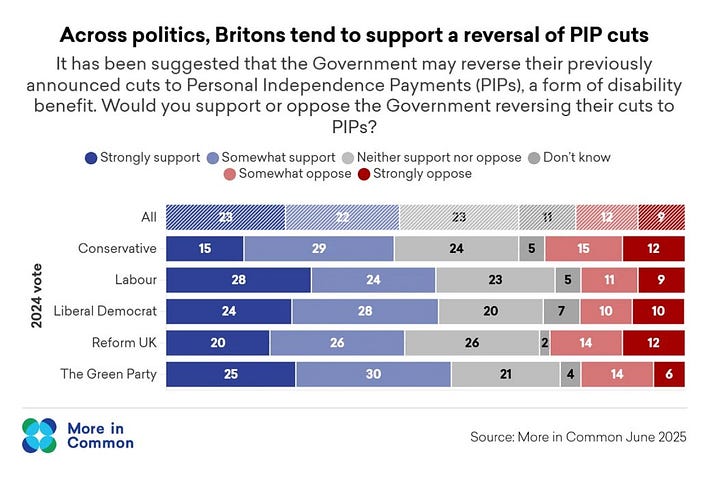

Facing the prospect of a full-blown revolt—and an embarrassing defeat—the climbdown was swift, if not entirely coherent. All current recipients of Personal Independence Payment (PIP) will now remain on the existing system. The controversial new criteria, previously expected to apply almost universally, will be limited to new claims from 2026 onwards. Existing Universal Credit health element claimants—and any new ones meeting the most severe conditions—will have their incomes “fully protected.”

A ministerial review of the PIP assessment process will now be conducted in-house, led by the Minister for Social Security and Disability. Meanwhile, the government pledged to bring forward additional funding for the Access to Work scheme.

On paper, initial suggestions appeared to suggest it was a full U-turn. Concessions like these, remember, were dismissed as “noises off” earlier in the week.

And yet it still doesn’t appear to go far enough—or make sense. The most obvious problem is that variable, progressive, and chronic conditions don’t obey calendar dates, and nobody can predict when, or if, they are about to become so ill that they require state financial support. The future still looks bleak for anybody becoming disabled or with health expected to worsen in the next year or so.

It’s also essentially a two-tier system for current and future disabled people. Yet a person’s health doesn’t become less complex or disabling simply because they applied for help in 2026 rather than 2025. The reforms, even softened, still landed as cruel, arbitrary, and ill-thought-through. Hastily issued and oddly framed, the concessions looked more like damage control than good policy, and moreover, MPs were still being asked to vote without full information on the impacts—a major red line.

As such—

What happens next will determine whether this was a passing storm—or the beginning of something far more destabilising.

Even if Starmer weathers this rebellion—as leaders sometimes do—the damage may not lie in parliamentary arithmetic, but in public perception.

Welfare reform, once the third rail of British politics, now floats in a strange no man’s land: too toxic to campaign on honestly, too tempting to leave untouched. Even among Labour’s dissenting MPs, there is broad consensus that reform is needed. Just… not like this. Evidently.

And so, as Labour contorts itself trying to reconcile fiscal conservatism with moral rhetoric, the electorate watches—warily, and with thinning patience.

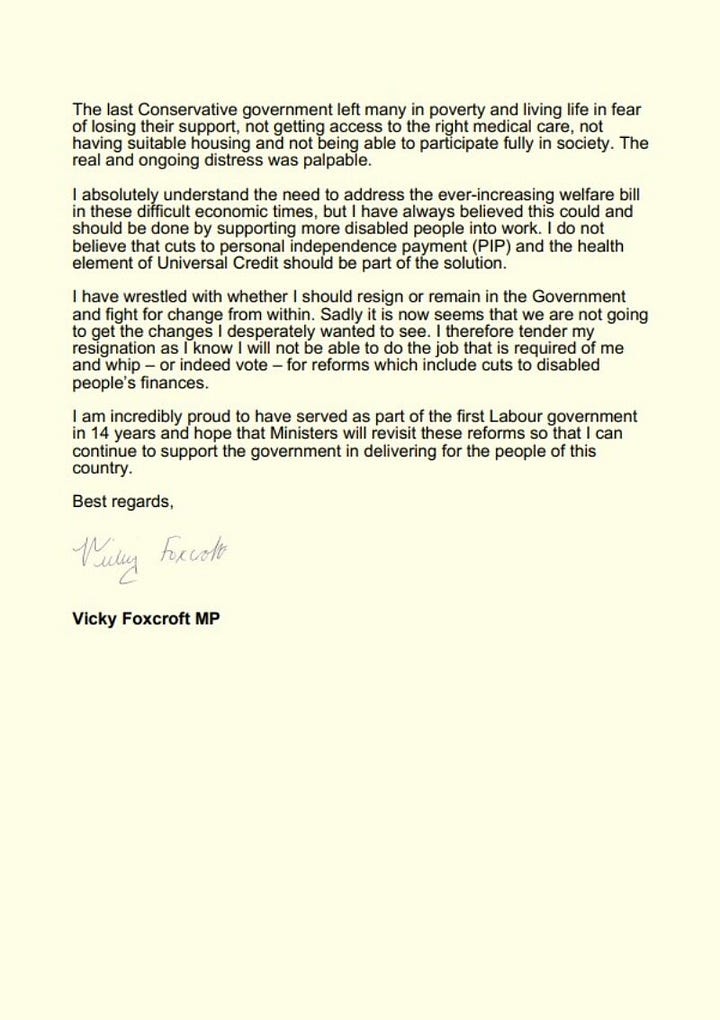

Indeed, polling suggests most voters oppose the government’s plans or believe they’re simply out of step with public opinion.

At this point, we reach the voter dichotomy stage where disillusionment calcifies; this page wearily turns to the other polling—courtesy of YouGov, four years out [!] from any general election—that suggests Reform might provide the solution.

And yet Reform’s welfare policy—such as it is—offers no real escape route either, if one reflects on the thinly sketched out policy commitments mentioned in their ‘Contract for the People’. It reads as economically illiterate (as per virtually every other policy they compass-carve onto the back of a fag packet), is casually cruel and written more or less as an afterthought. If enacted, it would likely intensify the very harms Labour’s rebels are now trying to prevent.

Still, clarity, anger, and a vacuum where principle used to be—that’s often enough. And so Reform rises.

It’s a paradox that, in despair at Labour’s betrayal on welfare—and it is a betrayal; regardless of concessions, nobody should forget what they tried to do—voters could end up electing something even worse. This is how consensus dies—slowly, bitterly—and nothing better rises to take its place.

A governing party in retreat. A populist right in ascent. A public increasingly convinced no one in Westminster speaks for them.

The crisis, then, isn’t just about leadership. Or policy. It’s about belief—what’s left of it—and how quickly it’s draining from the system.

On welfare, in particular, we are trapped: between a Labour Party that promises to govern like adults but behaves like gaslighting parents; a Conservative Party too traumatised to function; and a Reform movement whose big idea is to make the ugliest bits of Thatcherism sound like a pub fight.

Welfare—once a moral question—is now a spreadsheet problem.

And voters—those fickle, maddening, hopeful people—are left rummaging through the ballot like it’s a lost property bin, praying something in there still fits.

Democracy, it turns out, does offer choices.

Just not necessarily good ones—and even they can evidently change once they become unpopular. So much for conviction.